Many ESG topics are interconnected, making it difficult to look at them in isolation. The domain of ESG stretches across a broad range of themes that are just as complex as they are far-reaching. To truly understand how society is evolving on ESG, Lauren Demar goes beyond a superficial understanding of the subject in China.

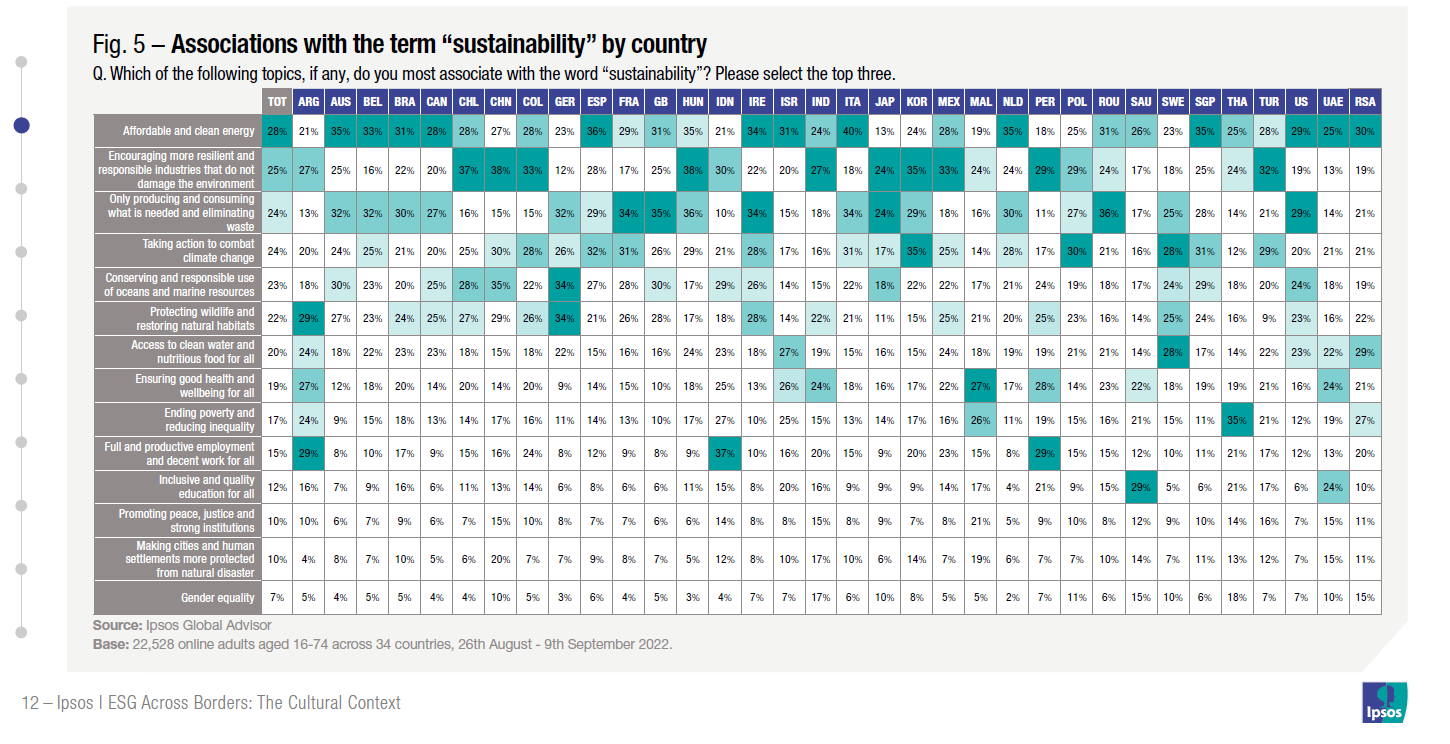

On average globally, almost a quarter (24%) associate sustainability with “only producing and consuming what is needed and eliminating waste”. In China, there is a stronger association (38%) with “encouraging more resilient and responsible industries that do not damage the environment” and at the same time, “conserving and responsible use of oceans and marine resources” (35%).

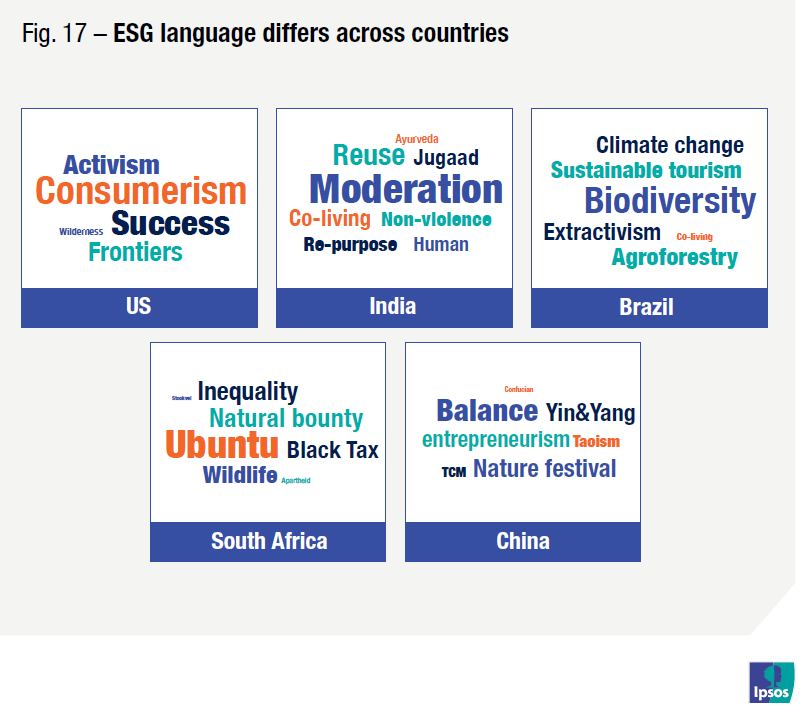

China’s culture is one of balance, regulation and moderation: yin and yang, Taoism, Confucianism. Traditional Chinese medicine revolves around taking the best of nature and sharing that benefit with people and the surroundings. Many of China’s cultural festivals concern nature, whether it’s the moon, harvest, water or the seasons.

At the same time, there is a strong focus on entrepreneurism and state capitalism, which often works at cross purposes to ESG mandates.

The 1990s and early 2000s – the peak of China’s economic development – was a period of unbridled entrepreneurialism. This led to many ESG breaches: contamination, pollution, deforestation, unethical and environmental practices around sourcing and processing. But Chinese people began to see the severe threat to the environment, even to their personal health and safety. The environmental aspect of entrepreneurialism has therefore become an urgent imperative.

Three cultural dimensions of ESG in China

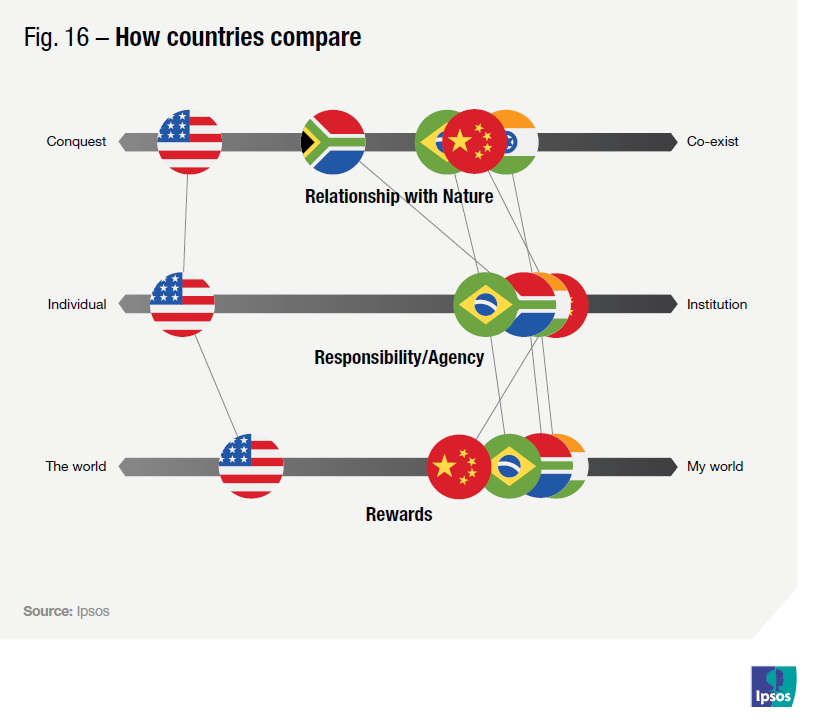

Studying the patterns, history of practices, types of ESG initiatives, popular sentiments and political policy, we identified three cultural dimensions that are shaping attitudes, perceptions and behaviour around ESG in the local market. Our analysis points to a huge variance when compared with other countries in how the priorities land within ESG and what is likely to drive investment into ESG related initiatives.

The following cultural analysis is a synthesis of all our research. Mapping our case study countries on to these three dimensions illustrates the need to take a unique, tailored approach to advancing ESG topics within each country.

In terms of the three drivers that shape the culture of ESG, China’s relationship with nature is characterised by co-existence, balance, and a need to be respectful and mindful of how nature is used and engaged with.

Because the government is such a big agent and trusted to do its best, and because China is an extremely collectivist society, the Chinese place responsibility to take the lead on addressing ESG issues with institutions – not just the government but also the business and private sector too.

Individualistic cultures like in US take on a personal onus to make a difference in any small way, believing it is as much a matter of choice as it is a duty. Collective cultures however, view any action as the prime responsibility of institutions. There is strong association of the environmental discourse with western/developed countries – and a feeling that some of the obsession with environment/climate is alarmist and impractical. With the high clutter of ESG messaging, collectivist cultures like in China are well aware of the need to be more mindful of the environment. But they also see the benefit of progress from modernisation and extractivism and value the livelihood and prosperity it brings to more people. And in this context, it helps to delegate the responsibility of the more urgent imperatives to the institutions. China believes that to make true impact, there is a need for collective action; individuals being seen to have limited agency.

An example of how this works is in the adoption of the European standards of pollution control and limiting emissions for the automotive sector. Compliance here is seen as not only being kinder to the environment but also as a way of making China's manufactured goods acceptable for developed export markets – aiming for not just eco prudence but also commercial benefit. They therefore look to the government and business to lead the way. There is a strong implication for partnerships with business and policy action from government.

When it comes to rewards, there is more of a balanced picture. While there is a slight lean towards prioritising actions that bring a benefit to individuals’ immediate community, this is increasingly coupled with an awareness and attention towards the need to be ESG compliant, especially when it comes to personal wellbeing and similar health issues. So there is a growing commitment to moving towards longer-term rewards too.

Our 2022 segmentation study of consumers and their attitudes towards ESG finds that China has one of the highest proportions of Pragmatists – people who are practical and pragmatic in the way they adopt practices around ESG into their everyday lives. (Consumers can be split into five segments based on what they feel and how they act: Activists, Pragmatists, Conflicted Contributors, Busy Bystanders and Disengaged Denialists.)

This is not surprising, as pragmatism is a value strongly embedded in Chinese culture. In looking to address ESG issues, the Chinese prioritise innovative solutions that can be easily adopted which results in a lot of green tech e.g. electric vehicles.

We also see cultural differences emerge through the choice of language people use to speak about ESG in each country: (China: 'balance', US: 'consumerism'; Brazil: 'biodiversity'; India: 'moderation'; South Africa: 'Ubuntu').

In looking to address ESG issues, the Chinese prioritise innovative solutions that can be easily adopted, which results in a lot of green tech.

Alibaba’s forest campaign is a prime example of success through smart innovation. Alibaba gamified ‘green behaviours’, awarding Alipay users with ‘green energy points’ whenever they made low-carbon lifestyle choices e.g. taking public transportation or holding video meetings instead of commuting to the office. The user can see their points building up in the form of a virtual tree growing on their app. Once users have accrued a certain amount of points, the company plants a real tree.

This tapped into the belief that we all need to do something to help the environment, allowing consumers to drive reforestation action and commit to participation, contribution and achievement. This is typical of how the Chinese look for a smart, innovative way, using technology, to address an issue – nothing is unsurmountable.

Historically, there are many practices around the E of ESG. Take traditional farming – China is famous for terrace fields, the canal system, following lunar calendar cycles for farming and planting, the concept of feng shui and harmony with different elements like water, wind, wood, metal, so on and so forth.

To a lesser extent, S has also been important, especially for companies operating in China. In a market with a collectivist tendency, consumers expect brands to act when a major public disaster happens e.g. an earthquake or a flood. International brands in China will need to take account of these expectations to achieve brand success.

Increasingly, we see a growing skew to health and wellness coming through, especially in the form of holding businesses accountable to ensure that they are doing healthy sourcing and that they are not damaging the environment in their processes. This has become increasingly important, with consumers willing to pay a premium for brands that have better, safer and healthier sourcing and environmental practices – especially in categories like infant formula or food and beverages. We also see growing trends in social sustainability surrounding the treatment of people in the workplace, labour laws and gender equality.

Although a large economy, China’s development has been unevenly distributed and in many regions the living standards are still yet to be improved. Several years ago, the northern province of Hebei put in place a complete ban on the use of coal to heat homes, in an attempt to improve air quality and meet environmental targets. But many villages had not been able to convert to gas, and alternative green energy was simply not ready for less developed areas. Many homes were left without heating in sub-zero temperatures. The incident triggered huge anger among the general public who urged the Chinese government to find a better balance between environmental protection and basic living rights. This balance and compromise is another key factor that characterises ESG practices in China.