It was impossible to realize it at the time, but it’s now clear that my descent down the slipstream of the disinformation rabbit hole happened because I joined the Lake Club swim team at the age of ten.

As the only sport I had the slightest aptitude for, watching the best of the best compete – particularly the women – has long been an enjoyable, if intermittent, pastime of mine (mainly because TV broadcasts of swim meets have historically been hard to come by outside of Olympic years).

The internet changed that, of course. For $7 per month, I can stream (pun intended!) many of the big meets on Peacock, NBCUniversal’s digital platform. By self-identifying online as a swimming fan, YouTube serves me up endless race videos. My iPhone sends me notifications that make it seem like the biggest news in the world is that the University of Virginia’s Gretchen Walsh has broken another NCAA record. And social platforms have long ago figured out that throwing links from Swimswam and Swimming World at me would prove catnip.

It was great there for a while.

My Feed turns toxic

But, recently, something fundamental – and ugly – shifted in the content I’m being served up, and it’s directly because of my interest in competitive swimming. I’ll explain the specifics shortly, but it doesn’t take much of a leap to connect the algorithmic dots – and then become extremely disturbed about how ineffectual the safeguards are that are meant to protect consumers, and brands from specious content, flat-out disinformation and online hate, especially during a year when many markets in the world head into important elections. Regretfully, research published late last year also warned various social media platforms have been scaling back their content safety efforts.

It is not, of course, just me experiencing issues (and alarm!) here. There are targeted disinformation campaigns everywhere, much of it aimed at riling up conservatives.

But, until recently, for all of the headlines about disinformation, I had experienced very little of it directly. Lately, the headlines are hitting me in a more profound way as much of my social media has morphed into a politically inflammatory hellscape.

So, the reason to go into detail about this on WARC – even though marketers are well aware of the online world’s dark corners – is to take what we already know, and illustrate what it actually feels like to suddenly find yourself awash in misinformation. It’s a very different mental space to be subjected to a constant barrage of untruths.

How an earnest, enjoyable interest led here

In 2022, a University of Pennsylvania swimmer named Lia Thomas became the first transgender person to win an NCAA Division 1 title, claiming top honors in that year’s women’s 500-yard freestyle. Ever since, Thomas has become a kind of Rorschach test for how one views fairness in women’s competitive swimming.

I’m not here to unpack that controversy. All I know is that, a few months ago, a post showed up on my social media from an outfit called SpaceX Mania, saying that Thomas hadn’t made the 2024 US Olympic team, which, if you follow the sport, you know is not true: The team won’t be picked until June at US Olympic Trials, and Thomas isn’t even competing.

I checked the post’s comments. Yes, it was a cascade of posts seemingly celebrating this “news”, but that’s not why I checked them – it was to see if people believed the article was true. And the vast majority of them did.

As a reporter, the original post was a trigger. I wrote a comment debunking it, which I’m now sure cranked the disinformation machine into high gear. Since then, I’ve been served dozens of false posts involving Thomas, often pitting her against Riley Gaines, an NCAA women’s swimmer who was particularly outspoken about Thomas’ competing in the women’s swimming events in the NCAA.

In the alternative universe my social media has become, the NCAA has stripped Thomas of her medals and given them to Gaines, and Gaines has made the Olympic team – but Gaines doesn’t appear to be competing at Olympic Trials, either.

And the disinformation in my feed keeps metastasizing. Some recent lowlights:

- The “You Can’t Cancel America” Tour Sold Out in Record Time, Easily Defeating Taylor Swift’s Overrated “Eras Tour” (Posted by “America - Love It Or Leave It”). This post is notable, in part, because the “You Can’t Cancel America” tour doesn’t exist and the story is of questionable “satirical” origins:

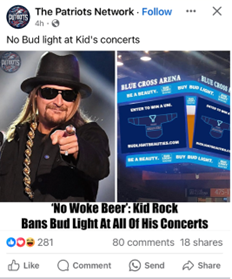

- “No Woke Beer” Kid Rock Bans Bud Light At All of His Concerts (posted by “The Patriots Network”) – even though the musician has announced his boycott of the beer brand is over:

- Beyonce’s “Country” Album Fails to Make the Top 100: “It’s a Complete Disaster.” (also posted by “America Love It - Or Leave It”) – in reality, the album was just released and is already breaking records:

And finally, this entirely untrue gem, served up as I was finishing this column:

(For more on how Bud Light, and others, fare during brand crises, check out this Red State vs. Blue State edition of the WARC podcast.)

It only gets worse

Most of these false posts employ a workaround so they can claim they are not, in fact, spreading disinformation and/or serving as a way to direct people to Made for Advertising sites (or “MFAs”): they post the “full story” via a link in comments.Sometimes, if you click on that link, you’ll discover that the troll farm source that published the content tags it as satire – which both stretches the bounds of satire, and downplays the post’s alleged intent in such a way that the damage has been done. This approach even has a name: hahaganda. (By the way, on the Space X Mania site, I found ads from major brands in financial services, retail, software, streaming and consumer-packaged goods.)

I don’t envy anyone whose job it is to police content. It truly seems like an impossible job, even with technological assistance. But what I’ve experienced recently shows how easy it’s becoming to trip the switch into very dark places, and if the amount of real estate being taken up by these dark places is expanding, users – and brands – should be aware.

The brand safety debate has already been through several iterations, complete with eye-popping survey results about the risks of failure, the use of tech-led solutions like blacklists and even high-profile advertiser boycotts of certain platforms deemed to be falling short. But real change has proved harder to come by.

When a problem is seemingly intractable, the will to solve it can fade. But if the bizarre transfiguration of my social media is any indication, marketers need to up their vigilance and be part of the solution, even if their motive is only to save themselves. This is especially true as a combination of artificial intelligence and elections means the amount of sketchy content on the internet they are unintentionally financing is only going to get worse.

As the onslaught of misinformation I’m subjected to has continued, it’s a constant reminder of some of the advice given to brands late last year in the ANA’s Programmatic Report, which – granted – only focuses on the open web. One is the importance of inclusion (not exclusion) lists, which can serve to protect brands. Many of these posts above, even if they claim to be from different groups, appear to be from the same so-called publisher. So, if, for instance, the site “America - Love it or Leave It” was excluded from places where a marketer would want their brand to show up, all the “publisher” would have to do is set up a new site with the same sketchy content.

A related piece of advice is to create a clear path from Supply Side Providers (SSPs) to sellers and publishers, with access to log-level data being one of the essential underpinnings to making this happen. It’s a big step forward toward dealing with the information asymmetry that can poison programmatic.

And perhaps, most importantly, brands need to realize the effective disconnect between cost and value, as they are prone to chasing cheap, and worthless CPMs, that end up on the MFA websites these social posts are meant to drive traffic to.

Fortunately, there’s a wealth of content about how to make better, more conscious media choices on WARC. They include the WARC Guide to conscious media investment, podcasts that unpack the ANA report and discuss other issues in the digital media ecosystem and much more.

Maybe telling this story, in all its strange and troubling specificity, can help brands better understand why they need to get their arms around disinformation – and how not to be part of it. As for me, I vow to never again comment on a social media post about people who didn’t make the US Olympic swim team, especially those who didn’t make the team because they aren’t even competing.