At a time when data privacy concerns are growing, people’s worries can take some unexpected directions according to Jamie Bartlett.

People are increasingly uncomfortable with how much businesses and platforms know about them. At the same time, however, all that information, when used in the way that is promised, delivers better products and services that improve their lives in various ways. It’s a conundrum.

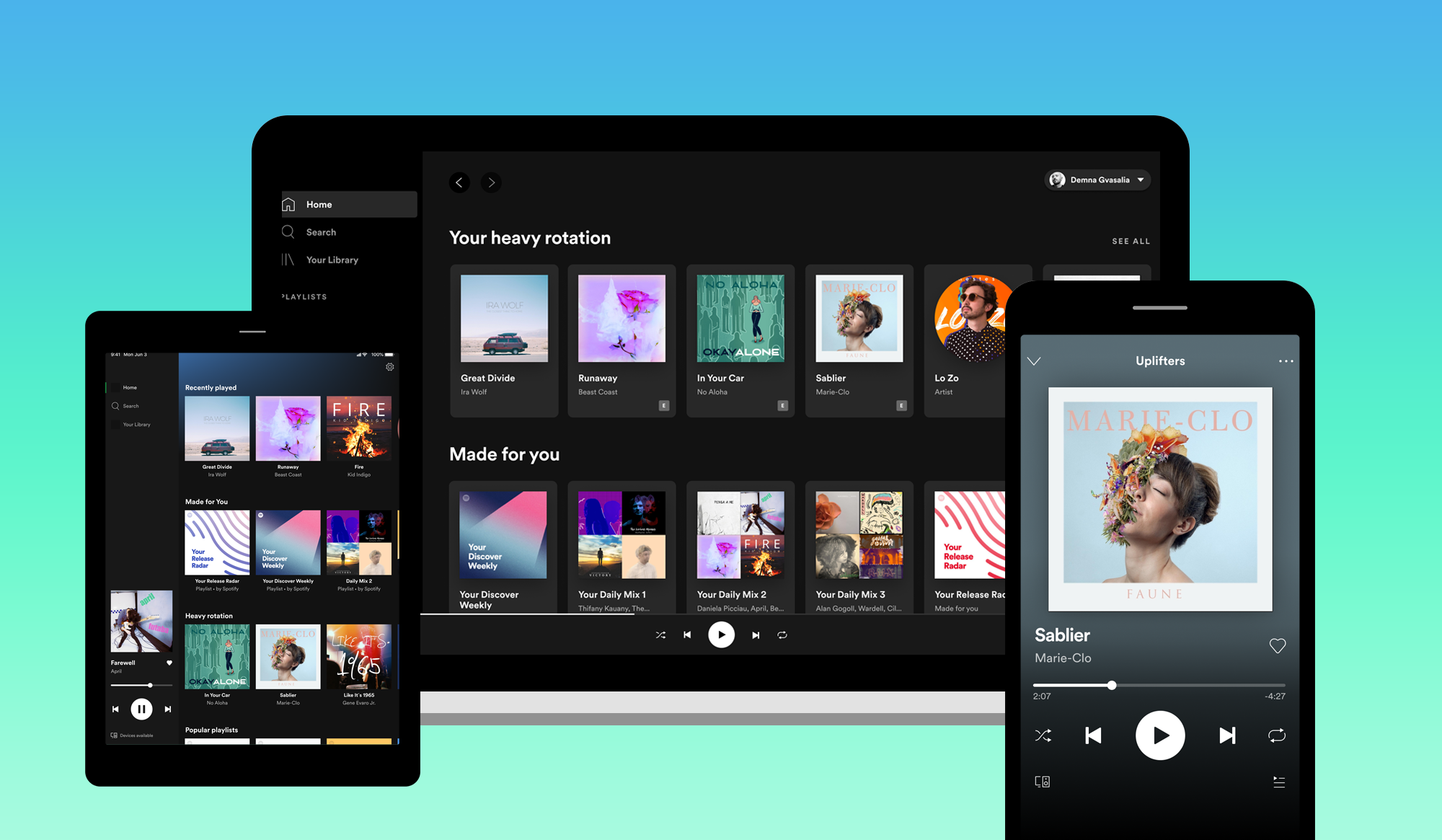

Take Spotify, for example, whose Discover Weekly and Daily Mix features are regularly held up as exemplars of how machine-learning algorithms can find new content and offer it to the user, confident that it’s hitting pretty much the right spot.

Spotify's recommendation engine has become a part of many lives

So for Jamie Bartlett, author, journalist and trained researcher, it was a bit of a surprise when Spotify recently chucked some U2 into the mix. “I hate U2,” he insisted to an audience at MRS Impact, the annual conference of the Market Research Society. “I felt a little upset and insulted,” he said; upset that a service he’d noted getting better and better had apparently failed; insulted that it should think he might like U2.

But then doubts started to crowd in. What if it wasn’t Spotify that was wrong? What if he’d secretly liked U2 all along? What if the algorithm had found out something he’d been suppressing?

“I’m sure recommendation therapy will become a big industry of the future,” he suggested: “learn about your true inner self by looking through the recommendations that you see.”

It’s a small instance of what he believes will be a bigger issue as more and more decisions are handed over to machines. When people don’t like or understand those decisions, they’ll want to have them explained to them, he pointed out.

In reality it’s not so much the decisions themselves – they’ll continue to be made by humans – as the decision-making process. “The danger is, we will outsource our critical thinking and we’ll just rely on machines to advise us how to do things; we’ll still be in charge, just leaning on what a machine advises us to do.”

Another scary prospect he raises is the use of smart fridges in electioneering. Data collection from this source enables analysis of the dietary habits of voters and inferential insights into mood – and when the best time might be to target them with certain types of messaging.

Hungry people tend to be in bad mood, people in a bad mood are more open to candidates who are tough on law and order; open your fridge at 6pm and that’s the cue for Jacob Rees-Mogg to pop up on your phone.

Crazy? No more than the idea of free social media platforms and the collection of huge amounts of personal data would have been to a voter at the turn of the century, says Bartlett.

“I don’t have a problem with mass data collection on people, and then using that to target commercial products for them,” he said. Elections are a very different matter, however. “Because what happens when every single person in the country receives a different advert from everybody else, through their smart fridge, their smart TV, based on 20, 30, 40 years’ worth of data? Can we still run elections in a way people think are true and fair?”

We’re always told that change is the only constant, but the speed of change in the online world is outstripping the ability of parts of the offline world to cope, whether that’s election law or people’s own sensibilities.

“This is going to create all sorts of issues,” Bartlett suggested. “And a lot of it is based on, I think, people not being comfortable or sure why they’re being targeted, how they’re being targeted or what’s known about them.”

It’s a potentially dystopian outlook for the 2030s, he acknowledged, although his view is inspired less by George Orwell and Aldous Huxley, more Franz Kafka and Philip K Dick – “a world where reality and truth are constantly blurred”.

And the problems are not insurmountable. “The task is to try to update, upgrade, change, improve the various social systems – the controls that we've built, the systems to help us understand how the world works.”

Cambridge Analytica felt like a shocking moment, but the problem is fairly easily fixed: every single ad that anyone runs during an election period is stored on a database that’s publicly accessible.

“There’s going to be millions of entries into that because everyone’s going to get a unique advert,” he acknowledged. “Then we build machinery to analyse it, so we can make sure that everyone sees what everyone else sees, so we know the ads that everyone is getting.

“This is a simple solution. It might not be the only thing we need to do but at least we can start.”